Farxiga. Hetlioz. Otezla. Zykadia. No, these are not the names of distant planets visited by the starship Enterprise. They're the brand names of medicines recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

If it seems as if drug names have been getting weirder, it's because, in some cases, they have. And they're likely to continue to, as the FDA approves new medicines at record rates, and regulations require a certain degree of differentiation from both other drugs and recognizable words—in any language.

"The more drugs that come out every year, the more novel the names need to be," said Scott Piergrossi, vice president of creative development at Brand Institute, which has worked with drug companies from Biogen to Allergan. So gone may be the days of simple, straightforward names like Prozac (approved in 1987) or Viagra (1998). "What you see approved today is very much a result of the environment in which we work."

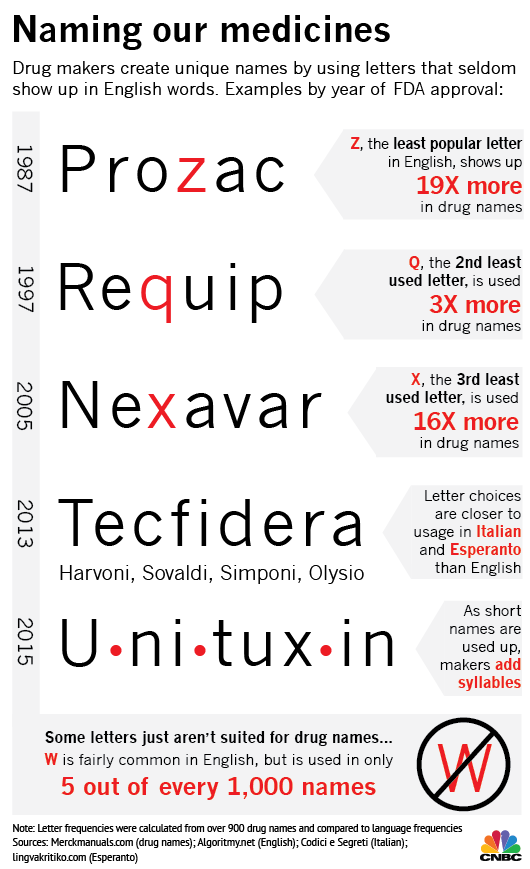

That may be why drug brand names have so many odd—or to use Piergrossi's preferred term, "novel"—characteristics. For example, drug names use the letter Q three times as often as words in the English language. For Xs, it's 16 times as much. Zs take the cake, at more than 18 times the frequency you'd find

them in English words. And Ws? You'll rarely see one in a drug name.

"For the most part, it's to get the name to be a bit more unique," Suzanne Martinez, senior identity consultant at InterbrandHealth, said of the proclivity for less frequently used letters. "Can you imagine if you had a name that had a Z, a Y and Q, and then you swapped those out to be an S, an I and a C? Suddenly you have what used to be a very unique name that now looks like everything else that's out there."

Steve Cole | E+ | Getty Images

Brand names of medicines have also been getting longer, according to Piergrossi. Take Tecfidera, the multiple sclerosis drug from Biogen approved in 2013.

"Nine letters, four syllables—the length is relatively novel," Piergrossi said. "But it's a fantastic name."

Only about 10 percent of drug brand names had four syllables in 2010, according to Piergrossi. That's now grown to 15 percent, as drugmakers search for ever-unique monikers. As for five-syllable drug names? They're coming. Take Jentadueto, a combination of two diabetes products sold by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

"Five syllables likely made it more approvable," Piergrossi said.

The FDA cleared 41 new drugs for market last year, the most since 1996. And while most of the agency's review concerns medicines' safety and efficacy, approval of the brand name is key as well. Some of the considerations the FDA makes:

- Does the name sound or look too much like another drug name? Names that can be easily confused can cause safety problems if they're accidentally swapped—this involves not just the spelling of the name, but also its pronunciation and appearance when written.

- Is the brand name too evocative or promotional? Names can't overstate efficacy, minimize risk or imply unsubstantiated superiority to other products, the FDA says.

Beyond regulatory concerns, there are trademark considerations, Martinez said.

"You have to make sure the name is proprietary, can be protected and isn't overlapping or on top of an existing name," she said. That includes products beyond medicines.

To add still another layer, drug companies have to beware of whether their brand names mean anything in any other language. Tecfidera, according to Adam Townsend, vice president of neurology marketing at Biogen, was almost called Panoplin. It had to go, ultimately, because "it was closely tied to terminologies in Nordic countries and Italy," Townsend said.

Tecfidera is the same brand name worldwide, a goal Biogen set out with from the start of its process, but it doesn't always end up that way. Rogaine, for example, is marketed as Regaine in Europe.

"In most of the rest of the world it's Regaine, but the FDA said not everyone will regain hair, so that's an exaggerative claim," Piergrossi said. "It's a very fine line we have to walk."

Chantix, the smoking cessation product in the U.S., is Champix elsewhere.

"You can hear in the name this idea of being a champion," Martinez said. "It's a little bit too strongly hinting at this idea of success or winning."

That fine line likely comes from an attempt to incorporate an emotion or concept into the name. For Tecfidera, Townsend said, Biogen wanted to convey freedom. MS is a degenerative disease that can lead to loss of coordination, slurred speech and paralysis. (Townsend concedes the connection between "Tecfidera" and "freedom" is a loose one. "It's just a process we go through to start to get names on the table," he said.)

Often drug names will differ based on what malady they treat: Diabetes medicines, for example, are increasingly named to try to engage patients "and make them feel they can be part of the solution," Martinez said. (Think Januvia or Invokana.)

Cancer drugs, on the other hand, are often named to communicate a scientific concept to a prescribing physician, such as the way the drug works. For example, Mekinist, for the MEK proteins it targets.

The research process can also turn up unexpected connections—to colors that connote death or blood, like black or red, in other languages or cultures, or to associations that are deal breakers for other reasons, Martinez said.

"When we do our name development, so many times we get our prescreens back and find a name means something terrible in German, or that it's a porn site that's famous in Europe and we can't use that name because of the domain name for the porn site," she said. "It happens all the time."

For those reasons, the naming process can start with hundreds or even thousands of names. Those then get whittled down to a handful that may be submitted for regulatory approval. The whole process can take from a few months to a few years; full legal screens can take six months, Piergrossi said. The cost, he said, ranges from $75,000 to $250,000 for developing a single drug brand name.

And as more drugs get approved, the name "never goes away," Martinez said. "That means drug naming gets that much more difficult."

So if you think they're tough now, get ready. The next wave of TV drug ads may include the phrase: "Talk to your doctor about Dvobvbh."

No comments:

Post a Comment